|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Working

with Scientific Data |

||||||

|

Editor's note: The following article was submitted by an early career epidemiologist. We look forward to presenting additional pieces with a unique perspective on their topics in the coming months. To submit an article for consideration please send it to: info@epimonitor.net Author: Wanyu Huang, PhD, MS I have fallen in love with finding metaphors to understand and interpret what I learned from when I was a high school student. Back then, physics was one of my favorite subjects, and I said that Newton's Third Law of Motion (the one that claims the equal and opposite reaction) was a perfect metaphor that persuades us to treat our lives the way we want to be treated by our lives. Years later, from 2019, I turned my path to music for my PhD journey in Epidemiology (I have been playing the violin for over two decades from a child and still love to play, now)- through which I got more systematic scientific research training. I have been having fun thinking about how working with scientific data inherently relates to interpreting and playing music, wondering if I would be able to see a systematic connection between them, as well. After a few years, it turns out that the process has been helping me out a lot - including but not limited to developing more thoughtful designs of scientific studies, having better organization of analysis plans, conducting more efficient data analyses, as well as gaining more confidence when self-evaluating the accuracy of my research results. Here, I would like to present the key parallels (or analogies) that I have thought about, in between conducting scientific (in my case epidemiological) studies and the routine for musical practices.

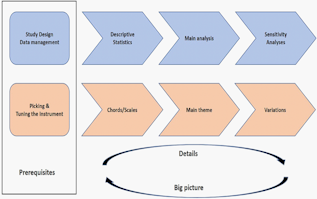

Main theme and variations We all remember the song Twinkle Twinkle Little Star from our childhood when we started to learn the alphabet. If I treat scientific data analysis as composing a musical piece, then a brief and straightforward set of analyses can be a great one, like a good song that everyone knows. Later, people may write many variations on it, in diverse ways and on different musical instruments. Nevertheless, all these variations develop from the main theme. Analogously in scientific data analysis, no matter how seemingly different sets of sensitivity analyses address the main study question from different perspectives, they shall be all pertinent to the main study question asked - and correspondingly, the descriptive statistics tailored to the main study question. Variations for the main theme, in musical context, come in diverse formalities. And these composing 'techniques' are used either by themselves or altogether. Musical composers can make a change for the tempo (slower theme to a faster variation, and vice versa), impose a tweak on the tune (a major key to a minor one, and vice versa), alter the dynamics, and/or simply add some interesting 'decorations' to enrich the main theme - including, but not limited to building up chords, overlaying overtones, etc. There are so many (indeed, almost infinite) ways to compose variations. In my musical learning experience as a violinist, the most impressive related episode dates back to high school, when I was sixteen. By then, I was starting to pick up the Chaconne in D minor, by Johann Sebastian Bach. As one of his greatest masterpieces of his sonatas and partitas for solo violin (BWV 1001 - 1006), it is quite lengthy and technically demanding - including appropriate demonstration of chords, dynamic contrasts, and good control of sound. I was provided with a lot of guidance to tackle a variety of technical difficulties - nevertheless, the single most important piece of advice was that I should always bear the 8-measures melodic line (i.e., the main theme) in my mind. We are all prone to instantly recognize that musical variations make the tunes more beautiful, the most important aspect is, nevertheless, that through the demonstration of variations, we remember the main theme deeper in our heart. A similar workflow happens when we deal with scientific data. In analysing scientific data, we perform additional sets of analyses besides our primary results, by which we call them 'sensitivity analyses,' to make sure that our results are robust and believable. This is what we get from our scientific training. To put my doctoral work into the musical context, the 'main theme' was to evaluate how different outdoor environmental factors (e.g., air pollutants, pollen) independently and jointly related to (or potentially affects) children's respiratory health (asthma exacerbation) in an urban setting. When it came to a more detailed picture, the 'variations' included assessing alternative definitions of cases, subgroups of different types of visits (outpatient, ED, hospitalization), as well as the scope to which the adjustment of additional confounders (e.g., other co-pollutants) affected the main relationship of interest [3]. In addition, I know that defining timing (i.e., which exposure precedes, which follows; how long is the latency period) [4], as well as the environmental exposures used and their level of precision are essential, which always deserves more exploration [5]. Sensitivity analysis results never appear the same as results from the main analysis, but are meant to reinforce the big picture that describes the relationship between environmental exposures and population health, which calls for alleviation of related environmental risk factors for better health prevention. Picking up a good musical instrument One of the pre-requisites of playing a good piece of music, without doubt, is choosing a good musical instrument that fits the characteristics of music. In many situations, multiple musical instruments can all be suitable for playing the same tune, however some simply do not work out (e.g., the violin may not play a tune as low-pitched as the double bass). In this, composers keep in their minds about the strength and limitations of each musical instrument - and choose the one that suits the best to create a specific piece of music. Each research area also has different study designs (which we also, sometimes, call tools or instruments) to conduct scientific research. We compare those study designs and choose the best that is suitable for the study question. More 'tools' are emerging nowadays - we are getting more options and need to choose more judiciously. Tuning the musical instrument After I tune my violin, the tune I play will be as expected, upon placing my fingers accurately on the finger board. Analogously, performing high-quality data management is essential in conducting good scientific data analysis, which cannot be overlooked. We should be clear about the structure of the data: what is the exact meaning of each variable? Where did they come from, and how were they processed? An iterative process When I practice my musical instrument, I go back-and-forth in between the different musical pieces and the basics (e.g., scales), to make the practice more efficient and fun. Similarly, when I am in the process of working with data to answer epidemiologic questions, I constantly remind myself of the descriptive features of the study population. It may be intuitive to think that the flow of working with scientific data goes exactly as what is in a manuscript - but indeed, I perceive it as an iterative process. We do not need to know about every descriptive feature of the study population before diving into formal analysis; and when we go into the details of the analysis, we also need to keep the big picture in mind from different descriptive characteristics. I always got much more confidence in my own results - because an iterative process between the big picture and the details not only helps me get more smoothly into the data analysis, but also enables be to check if the results are reasonable. Last, if there is anything for us to be cautious about, it is that the iterative process is not equivalent to picking up the results we desire - but simply: we do not need to know about every detail of descriptive feature of data before diving into formal analysis; and when we get more detailed in the analysis, we also need to keep the big picture in mind. Conclusion Throughout these years, I have really loved the process of putting aspects of scientific research parallel to the musical context that I started getting exposed to from my childhood. I found it a very efficient and fun way to build my knowledge frameworks for conducting epidemiological research. As a nutshell of intellectual curiosity, music served as an artistic metaphor. And now I am starting to see a systematic connection between science and music. Discerning the connection across different disciplines is essential in understanding a scientific discipline and eventually contributes to the establishment of new theories - with no exception for epidemiology[6]. Therefore, I would bravely assert, that if even a seemingly distant dialogue between music and science can be established, then we shall not be hesitated to discover more connections that await us - from other disciplines/aspects out in the world in our lives, and to close those gaps with regards to how they interplay. All these, taken together, will not only be an intellectual-rewarding journey for us, but a process in accumulating evidence towards continuing learning to conduct scientific research and teaching/mentoring the next generation. ■ Acknowledgements: I always owe my sincere gratitude to Dr. Anneclaire De Roos, who mentored and guided me throughout my PhD journey at the Dornsife School of Public Health at Drexel University, from which I accumulated invaluable experiences and thoughts for conducting scientific research. I am also truly thankful to Dr. Neal Goldstein, my instructor for the Epidemiology PhD Seminar class during my second year, for taking his time knowing about and discussing these ideas with me. Last, I greatly appreciate the effort of Dr. Marc Weisskopf at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, who supported me through proofreading and sincerely providing editorial suggestions. REFERENCES: 1. 1. Fox, M.P., et al., On the Need to Revitalize Descriptive Epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol, 2022. 191(7): p. 1174-1179. 2. 2. Hayes-Larson, E., et al., Who is in this study, anyway? Guidelines for a useful Table 1. J Clin Epidemiol, 2019.114: p. 125-132.

3. 3.

Huang, W., et al., Effects of ambient air pollution on childhood

asthma exacerbation in the Philadelphia metropolitan Region,

2011-2014. Environ Res, 2021. 197: p. 110955.

4. 4.

Huang, W., et al., Do respiratory virus infections modify

associations of asthma exacerbation with aeroallergens or

fine particulate matter? A

time series study in

Philadelphia PA. Int J

Environ Health Res, 2024. 34(9): p. 3206-3217. 5. 5. Weisskopf, M.G. and T.F. Webster, Trade-offs of Personal Versus More Proxy Exposure Measures in Environmental Epidemiology. Epidemiology, 2017. 28(5): p. 635-643. 6. 6. Krieger, N., Epidemiology and the people's health: theory and context. 2024: Oxford University Press.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||